Before you get into this, I am sorry, this post is long, it may or may not make a lot of sense, and I am sure a lot of people would argue with what I have said. Carry on.

Indestructible miter. A bold claim I know. Indestructible and miter are words that do not often go together. The miter opened up, this mitre won’t close, why did I choose to use these damn miters, all a lot more common to hear.

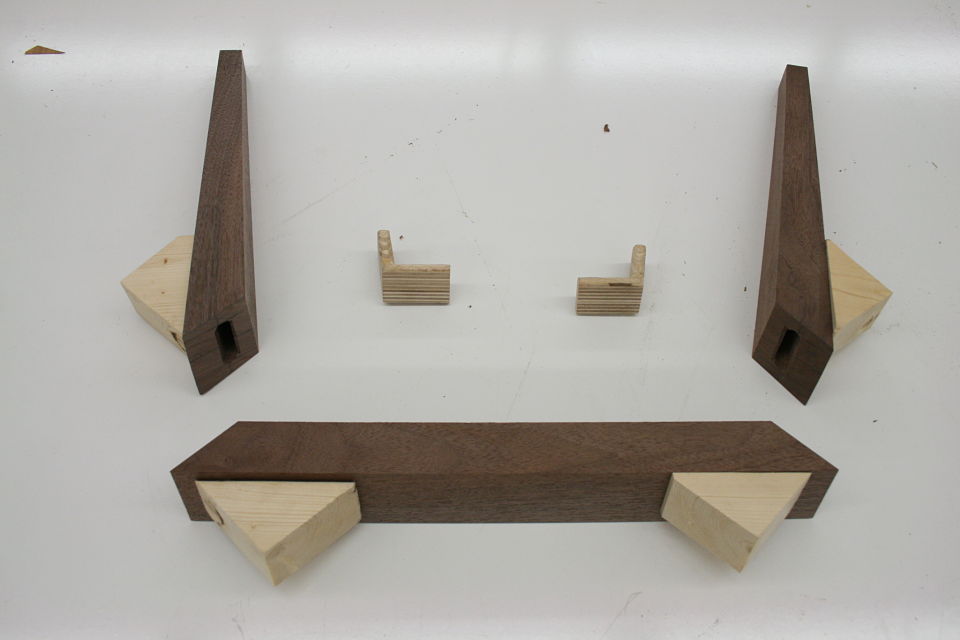

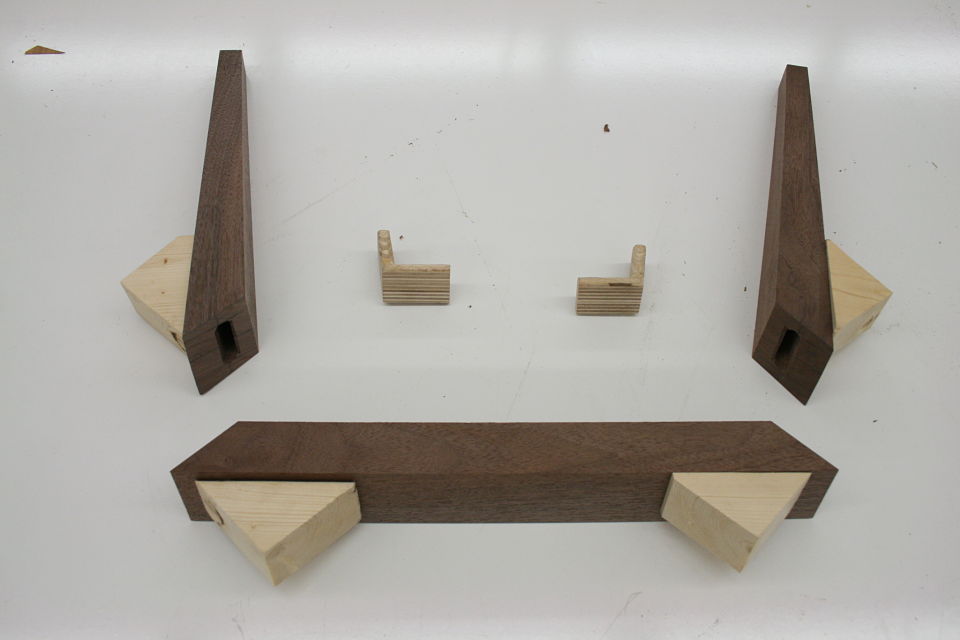

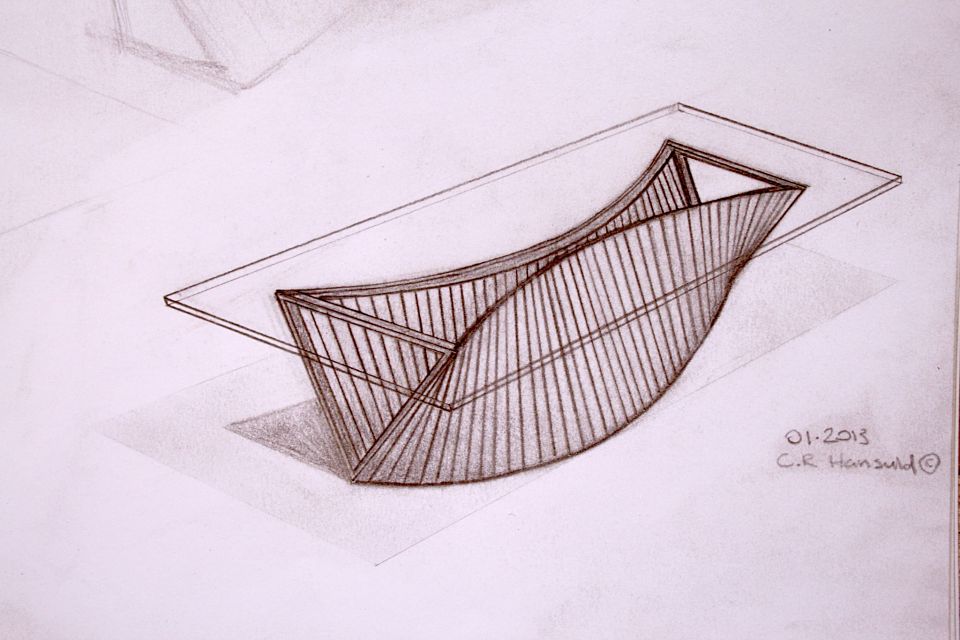

But bear (bare?) with me here, what you are about to see below is an adapted version of a joint that was introduced to me as “the indestructible miter.” Or if you would like to take it down a few notches on the “awesome scale” the plywood L-tenon. It is exactly as it sounds. Plywood and indestructible are again two words we are not used to hearing together, but it is the perfect material for an L-Tenon.

Why you may be asking? Alternating grain direction for maximum strength. It is really just that simple. Miters are difficult to join because of the amount of end grain in the joint (end grain has no glue strength). This is why typically we cut keys or splines in a miter joint is to gain some “face grain glue surface.”

But isn’t half of plywood end grain? Sounds like you are going against your own advice….

You got me, it’s true, but the other half is perfect face grain to face grain glue surface. And the end grain portion on the one side of the miter is the face grain on the other part of the board. Tricky no?

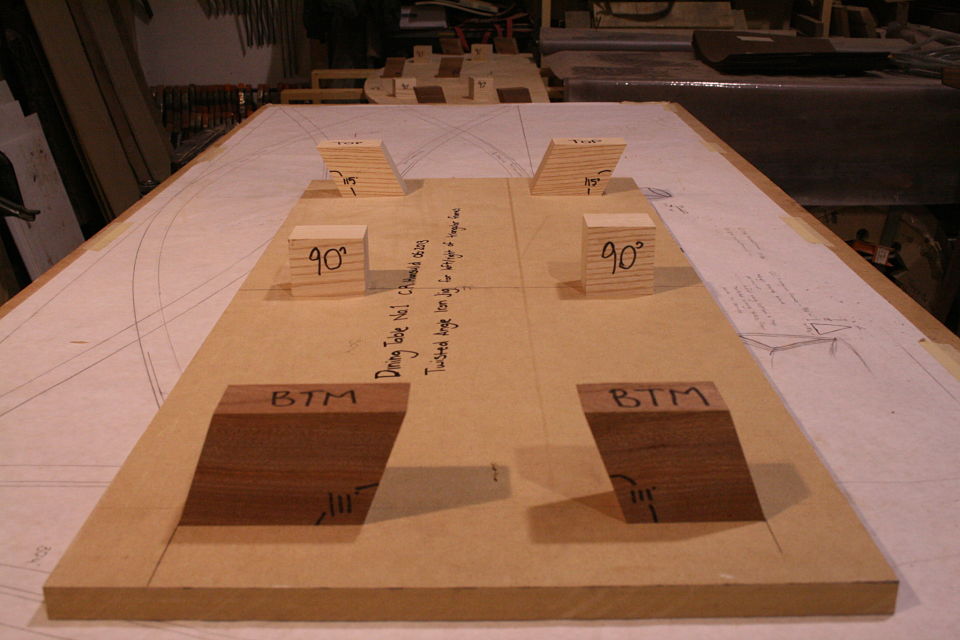

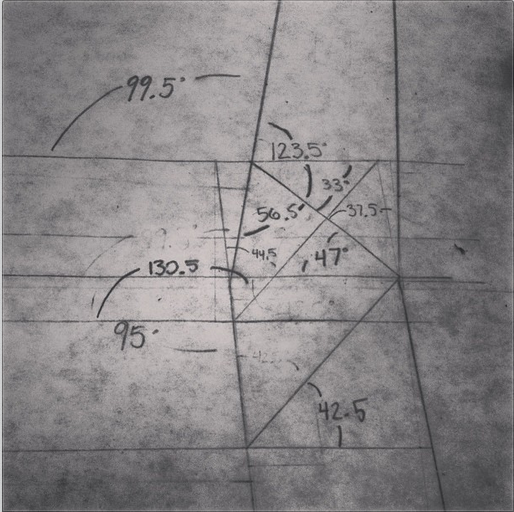

But there’s another part to this equation. Keys / splines and most other miter “joinery” has very little “depth” into the actual boards. This may be okay for little boxes, or a casepiece, but chairs are under stress, a lot of stress, and they need something a little more substantial. The “L-Tenons” allow me to route deep (in this case around 2″) mortises into both parts. What I end up with is a 2″ worth of tenon (and a longer bit could get me more) into either side of the miter. Quite a bit of depth all things considered. Couple this with the alternating grain and you have a joint that is “indestructible,” relatively speaking anyways.

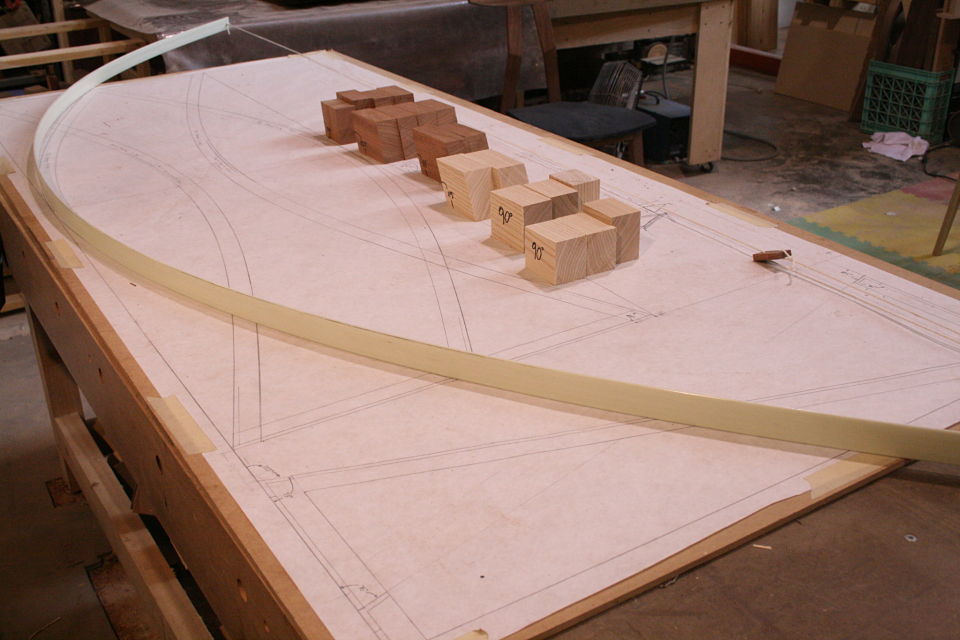

This may be a lot to take in at this point, hopefully the pictures will clear it up some. For the record these are a bit of a variation on your standard “Plywood L-Tenon” as they are obtuse angles and canted as well. Testing as to the actual strength will commence once the stool is together. Stay tuned.